English translation by James E. Irby

Russian translation by Eugenia Lysenko

One day, at lunchtime, I mentioned that “The Close”, a fifteenth century timber-framed cottage at the corner of Castle Street and High Street, was in fact only a half of the house built elsewhere, say in Kent but don’t quote me on that, and brought to Saffron Walden with the second half left behind. I distinctly remember reading about that somewhere. After the lunch, I decided to look it up in the definitive, or so I thought, guide The Buildings of Saffron Walden by Martyn Everett and Donald Stewart. Nope. No mention of The Close, although the drawing of its oval “spider” window is there (p. v, under the table of contents). Then I realised that actually I read about it in the third volume of Down Your Street in Saffron Walden by Jean Gumbrell, a book that I have no recollection of bringing to Spain or, for that matter, disposing of. The subsequent web search neither confirmed nor refuted the alien origin of The Close.

A few weeks later, we were looking for another book that I am absulutely sure is still with us, even though the results of our hunt might suggest otherwise. Tamara proposed to put on hold the excavations in a hope that the offending book materialises at some random moment. It was at this point that the concept of hrönir came back from memory. Not that it was buried too deep, but still.

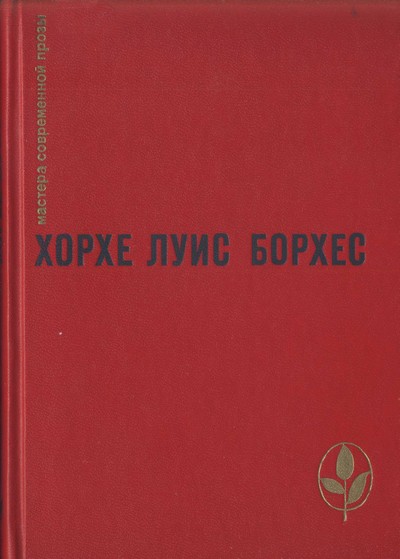

I discovered Borges in the 1980s, in the form of a book Хорхе Луис Борхес. Проза разных лет (according to Wikipedia, the first ever Russian edition of Borges). Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius was a short story that impressed me the most. It was mentioned there that in Tlön the lost objects could be duplicated — and “found” — by the sheer power of memory or imagination. These duplicates are called hrönir (plural of hrön). Now I needed to refresh my memory.

I opted for the Spanish original this time. As we don’t have a physical book, I found the story on the web and revisited the corresponding passage. It appeared to be funnier than I remember it in Russian. Why?

Hecho curioso: los hrönir de segundo y de tercer grado — los hrönir derivados de otro hrön, los hrönir derivados del hrön de un hrön — exageran las aberraciones del inicial; los de quinto son casi uniformes; los de noveno se confunden con los de segundo; en los de undécimo hay una pureza de líneas que los originales no tienen. |

Curiously, the hrönir of second and third degree — the hrönir derived from another hron, those derived from the hrön of a hrön — exaggerate the aberrations of the initial one; those of fifth degree are almost uniform; those of ninth degree become confused with those of the second; in those of the eleventh there is a purity of line not found in the original. |

Любопытный факт: в «хрёнирах» второй и третьей степени — то есть «хрёнирах», производных от другого «хрёна», и «хрёнирах», производных от «хрёна» «хрёна», — отмечается усиление искажений исходного «хрёна»; «хрёниры» пятой степени почти подобны ему: «хрёниры» девятой степени можно спутать со второй; а в «хрёнирах» одиннадцатой степени наблюдается чистота линий, которой нет у оригиналов. |

Could it be that the “original” sourced on internet is a (higher degree and better) hrön of that half-forgotten Russian translation? Or was it brought by the omniscient Google in the same fashion that it brings info about whatever we were talking about an hour ago? What’s the difference anyway?

I decided to re-read the whole story from the beginning to the end. Turned out I forgot almost everything, save the hrönir and a description of Tlönic nounless languages (this latter bit demonstrates Borges’s bilingualism which is completely lost in translation).

If in Tlön they can materialise things remembered, the reverse is also true:

propenden asimismo a borrarse y a perder los detalles cuando los olvida la gente. Es clásico el ejemplo de un umbral que perduró mientras lo visitaba un mendigo y que se perdió de vista a su muerte. |

they also tend to become effaced and lose their details when they are forgotten. A classic example is the doorway which survived so long as it was visited by a beggar and disappeared at his death. |

у них также есть тенденция меркнуть и утрачивать детали, когда люди про них забывают. Классический пример — порог, существовавший, пока на него ступал некий нищий, и исчезнувший из виду, когда тот умер. |

Do we live in Tlön already? (The world will be Tlön, wrote Borges in 1940.) Do the things we can’t find anymore dwell among other decaying hrönir? Can we use forgetting for declutter our living spaces?

As mentioned before, the non-existence of The New York Times Lola Flores quote did not prevent any Spanish periodical to reproduce it. If they keep repeating it for another 50 years, they may force the NYT to publish a clarification by virtue of which the famous phrase will indeed appear in this newspaper. Q.E.D.

What about The Close? The same thing really. Somebody will read this blog post and repeat the theory about the second half of the house; or maybe go as far as, say, Kent and build there the (improved) replica of the Saffron Walden original. Subject to planning permission, of course.

Back to the missing book. (It was right here, on this shelf. Or maybe it fell behind it?) On the face of it, the fact that we do remember it well and still can’t find it disproves the hypothesis that hrönir exist. But honestly, how well do we remember it? For one, we were not sure of its precise location or when was the last time we saw it. Not that well then. If I remembered literally everything that was written in the book, I wouldn’t need it in the first place. If I were looking for it to give it away as a gift, I would already mentally say goodbye to it. And so on and so forth, the possibilities are endless.

Isn’t the memory amazing? I can spend hours trying to recall a line from a song to no avail. I give up; half an hour later the line comes back, complete with full lyrics and a numbered list of variations which I didn’t ask for. One day, I hope, an unexpected cue will force the book back into existence.

No comments:

Post a Comment