introduction by Pilar Pedraza

I honestly wanted to like this book. Now that I finished reading it, I still like the idea of this book: to explore the rise and fall of femme fatale in art of the late 19th to early 20th centuries from the feminist perspective. Not the implementation though.

First, the style. If the author wanted to make a misery of your reading experience, she mostly succeeded. Long and convoluted sentences abound, as does the use of passive voice and first person plural albeit there is only one author*. Like this passage (p. 19):

Otros aspectos cuyos análisis también se echan de menos, y que ya hemos señalado líneas atrás, confluyeron asimismo en el desarrollo y creciente expansión de estas imágenes en la iconoesfera europea, que, si en un principio, en Dante Gabriel Rossetti y Gustave Moreau, fueron producto de eruditas fantasías canalizadoras de oscuras pulsiones sexuales, más adelante, cuando el mito femenino por ellos creado fue recogido por los «baudelerianos», fueron recreadas por estos agregándoles los rasgos de las femmes damnées y las femmes stériles del poeta, conformando una imagen que conectaría con la atmósfera de rechazo hacia el sexo femenino de su entorno social.

The word “perverse” and variations thereof (perverso, perversa, perversidad) are overused to the degree that they lose any meaning. In the chapter about Salome, the author insists on the absurd expression cabeza decapitada, “decapitated head”.

You’d think, once you plough through the text, great intellectual reward awaits. You may be disappointed. The “analysis” (another worn-out word there) of artworks could be boiled down to looking for — and finding — polarising stereotypes: Madonna vs whore and man/God/virtue/soul/spirit/reason/art vs woman/Devil/sin/body/matter/instinct/nature. Of the two dichotomies, the latter trumps the former: Madonna is still a woman and as such is inferior to a man. The recurrent themes are reduced to simplistic formulae such as woman = beast = evil, woman = monster = evil, woman = lust = evil, woman + redhead = evil, woman + power = evil, woman + sterile = evil, woman + homosexual = evil, woman = castrating = evil, woman = child = evil, woman = death = evil... You’ve got the idea.

The book is full of quotes in languages other than Spanish. I attribute this not as much to snobbery as to availability of Spanish translations to the author coupled with good old laziness. For example, on p. 225 Edvard Munch is quoted in Catalan because, the footnote explains, its source was a catalogue of Munch exhibition in Barcelona. Given that not everybody in Spanish-speaking world is fluent in English (French, German, Italian or, for that matter, Catalan), it could be nice to provide the reader with translations.

The volume I took from the library is marked as the 3rd edition (Ediciones Cátedra, 2021, ISBN 978-84-376-4134-8); on the same page, the first edition is said to be 2020. Yet according to Bornay’s bibliography, the first edition of Las hijas de Lilith appeared in 1990. I found what is called the 1st edition (1990) and the 2nd edition (1995) on Internet Archive. A handful of illustrations differ but the text remains essentially the same. Even the phrase “la segunda mitad del pasado siglo” (p. 50), “the second half of the last century”, obviously referring to the 19th century, has not been corrected.

Does it matter? Let’s check out the literature references. In this (2021) edition, the only post-1990 sources cited are Nana, Mito y Realidad (Madrid, Alianza, 1991) by Werner Hofmann, which is a translation of a German book Nana: Mythos und Wirklichkeit (DuMont, Köln, 1973), as well as Bornay’s own La cabellera femenina: un diálogo entre poesía y pintura (Madrid, Cátedra, 1994). The rest of the bibliography seems to be identical to that of the older edition. So we have to take any mention of “new”, “recently discovered”, “in the last years” and so on with a spoonful of salt (and subtract 30 years).

On a positive note, I discovered new (for me) artists. The book is printed on excellent heavy paper and most of the illustations are also of decent quality; it’s a pleasure to hold in hands. For the reasons unknown, several oil paintings are reproduced in black and white. I think it would make a good gift if it were available in hardback.

Now let us look at the pictures.

If the 1st edition (1990) shows a small fragment (just a face) of Judith II by Klimt on its cover, its 1995 follow-up features an illustration by Margarita Suárez Carreño, also of a female face. The cover of the 2021 edition is graced by the nude figure of Lilith (1889) by John Collier. No doubt, calculated to grab attention of a male passer-by like me.

The Rossettis

Whereas many painters of the era were, according to Bornay, either afraid of women or openly misogynist, this was not the case of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The author seems to be surprised herself when she writes that the painter’s relationships with women were “normal”, whatever that means:

nada hace evidente que albergase sentimientos de tipo misógino, ni ningún tipo de acritud hacia la mujer; en este aspecto, sus relaciones con el sexo opuesto fueron normales.

Considering that Bornay dedicates a lot of space to Rossetti and uses his paintings to illustrate most of the chapters, I found it strange that she never mentions the artist’s sister, the poet Christina Rossetti, while Gabriel’s wife, model and fellow artist Elizabeth Siddal only appears in a couple of endnotes. Wikipedia says:

By 1852, she had become Rossetti’s main model and muse, and he stopped Siddal from modelling for others. <...> Siddal seems to have inspired Rossetti, as he followed her in depicting the same subjects, and he reused her designs after her death.

I suppose, that kind of behaviour was deemed “normal”.

|

| Elizabeth Siddal, Self-portrait (c. 1854) |

If you are anywhere near London, it could be worth checking The Rossettis, an exibition at Tate Britain (until 24 September 2023).

Biblical figures

It should come as no surprise that Biblical women in art are almost always associated with sin, death and bad things generally. The trouble started with the first woman, Lilith...

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Lady Lilith (1872–1873) |

...and continued with Eve...

|

| Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer, Eve (1896) |

Forget that pious widow, saviour of Israel: fin de siècle Judith is a ruthless seductress. In contrast to many other artistic renditions of the story, the painting of Franz von Stuck shows stark naked Judith immediately before beheading sleeping Holofernes, with no helpful maid in sight.

|

| Franz von Stuck, Judith (1926) |

Although the Bible doesn’t say that Samson and Delilah even had a sexual relationship, the painting of Max Liebermann leaves no room for doubt.

|

| Max Liebermann, Simson und Delila (1926) |

Erika Bornay dedicates whole 13 pages to Salome. It’s curious how this relatively minor character who is not even named in the New Testament became so popular in literature and art. Gustave Moreau, in his 1876 painting, spared us the gory view of John the Baptist’s severed head: Salome is shown just at the beginning of her fateful dance.

|

| Gustave Moreau, Salomé dansant devant Hérode (1876) |

Classical mythology

Orpheus, after the death of Eurydice, ignored women but was taking male lovers. So, furios Thracian women tore him apart. In another version, he was killed by Maenads for refusing to entertain them.

|

| Émile Lévy, La mort d’Orphée (1866) |

Another Thracian woman, Phyllis, was waiting in vain for her husband, king of Athens Demophon, to return from wherever he was; in despair, she killed herself. Demophon eventually did come back and “when he embraced the lifeless almond tree into which she Phyllis was said to have transformed after death, it started to blossom”. Fair enough. Now observe Phyllis and Demophoön, aka The tree of forgiveness, by Edward Burne-Jones. It shows Demophon positively horrified when his presumably dead wife springs out of the blooming tree looking very much alive and trying to hug him back. Whether he was expecting any forgiveness, remains a mystery.

|

| Edward Burne-Jones, Phyllis and Demophoön (1882) |

According to Wikipedia, “in early Greek art, the sirens were generally represented as large birds with women’s heads, bird feathers and scaly feet”. Later, another — half-woman, half-fish — kind of siren appeared; this representation became dominant in European art. Bird-like sirens attack the Odysseus’ ship in the 1891 painting Ulysses and the Sirens by John William Waterhouse. On the contary, the 1909 painting of the same name by Herbert James Draper features a much more sexually attractive team of one mermaid-like siren and two perfectly human ones. I think Odysseus stares at the blonde, if only with his left eye.

|

| John William Waterhouse, Ulysses and the Sirens (1891) |

|

| Herbert James Draper, Ulysses and the Sirens (1909) |

Likewise, Sphinx (1904) by von Stuck depicts a nude woman that has no animal parts whatsoever. Maybe it is the way to say that woman is a monster even if she doesn’t look like it.

|

| Franz von Stuck, Sphinx (1904) |

The three Gorgon sisters on Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze look pretty much human. Rather having serpents for hair, their coiffures are decorated with just a few golden snakes. I suppose Medusa is in centre. According to Wikipedia,

In classical Greek art, the depiction of Medusa shifted from hideous beast to an attractive young woman, both aggressor and victim, a tragic figure in her death. The earliest of those depictions comes courtesy of Polygnotus, who drew Medusa as a comely woman sleeping peacefully as Perseus beheads her. As the act of killing a beautiful maiden in her sleep is rather unheroic, it is not clear whether those vases are meant to elicit sympathy for Medusa’s fate, or to mock the traditional hero.

|

| Gustav Klimt, Beethovenfries (1901, detail) |

The lady of Pornokratès is thought to represent Circe, a Greek goddess famous for turning men into animals. The pig she is walking on the leash could be one of her victims.

|

| Félicien Rops, Pornocrates (1878) |

In 2018, the J. W. Waterhouse masterpiece Hylas and the Nymphs was temporarily removed from public display in a misguided attempt to prompt some sort of debate; the decision was “influenced by recent movements against the objectification and exploitation of women” along the lines of #MeToo. A week later, following a well-deserved public outrage, the painting was put back on the wall.

|

| John William Waterhouse, Hylas and the Nymphs (1896) |

Voluptas is a Roman goddess of sensual pleasures, equivalent of Greek Hedone. Probably not life-threatening, although we don’t know much about her. (I found only a handful of classical quotes and no mention of Hedone in my copy of The Greek Myths.) In any case, Christianity did a fair job of imposing a cult of asceticism and sexophobia, so she must have been viewed as dangerous. In Franz von Lenbach’s rendition, Voluptas doesn’t look nearly as frightening as the painter’s own family.

|

| Franz von Lenbach, Voluptas (1897) |

A short, well written and entertaining take on misogyny in Greek mythology is provided by Clara Serra in chapters 5 and 6 of her Manual ultravioleta.

Historical Figures

Of all historical femmes fatales, Bornay chose three: Cleopatra, Messalina and Lucrezia Borgia. Although she does mention the watercolour by Dante Gabriel Rossetti where Lucrezia Borgia washes her hands (hygiene above all!) after poisoning her husband, the reproduction is not included in the book. I allowed myself to correct this oversight below.

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Lucrezia Borgia (1860–1861) |

|

| Alexandre Cabanel, Cléopâtre essayant des poisons sur des condamnés à mort (1887) |

|

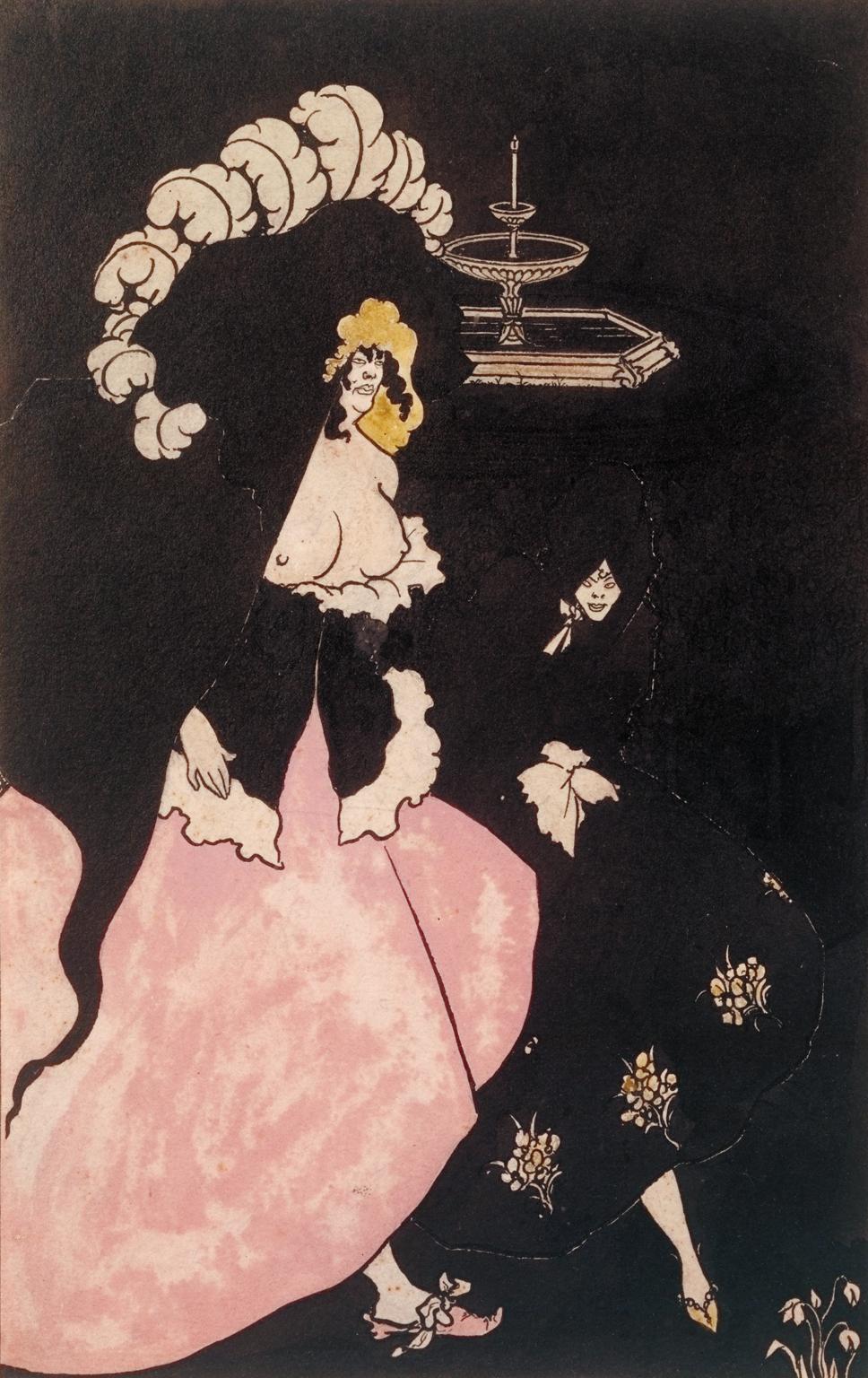

| Aubrey Beardsley, Messalina and her Companion (1895) |

Fictional Characters

Titania and Bottom represents a scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The women and children depicted are seductive, scary, or both.

|

| Henry Fuseli, Titania and Bottom (c. 1790) |

Britomart, a lady knight, is a character from The Faerie Queene, an epic poem by Edmund Spenser.

|

| Fernand Khnopff Britomart (1892) |

The 1880 painting of Gabriel Ferrier shows Salammbô, a fictional title character of the novel by Gustave Flaubert, engaged in ritual antics with her pet python.

|

| Gabriel Ferrier, Salammbô (1880) |

Dolce far niente

Relieved of truly hard work — say, slaving in the field — but far from being free, the bourgeois woman of 19th century finds herself with very little to do. To illustrate this persistent ennui, Erika Bornay quotes from the diary of Sophia Tolstaya (1 April 1863):

He <Leo> has his work and the estate to think about while I have nothing... What am I good for? I can’t go on living like this. I would like to do more, something real. At this wonderful time of year I always used to long for things, aspire to things, dream about God knows what. But I no longer have these foolish aspirations, for I know I have all I need now and there’s nothing left to strive for. So much happiness and so little to do.

No, not particularly femme fatale material. How about this (16 December 1862):

If I could kill him and create a new person exactly the same as he is now, I would do so happily.

Of course nobody could do that; why couldn’t she limit herself to the first part of the plan?

|

| John William Waterhouse, Dolce Far Niente (1880) |

Marie Spartali Stillman (1844—1927) is one of only two female artists mentioned by Bornay in Las hijas de Lilith. (Another one is Artemisia Gentileschi who lived in the period outside of the scope of the book.) And when I say “mentioned”, I mean there is a reproduction of Spartali’s 1891 painting, Convent Lily, to illustrate the maxim of Jules Michelet, “La femme est une religion” (“Woman is a religion”). Not a word about Spartali herself. Probably she was not misogynist enough to deserve a place in the text.

|

| Marie Spartali Stillman, Convent Lily (1891) |

Courtesans and prostitutes

Prostitution and prostitutes have been around for millennia. So what changed in the 19th century? Not much really except the sex workers, explicitly named as such, became acceptable subjects of Western Art. When it was first exhibited, Olympia by Édouard Manet caused a scandal precisely because the titular lady was not disguised as Venus or suchlike figure. What Bornay does not mention is that the model, Victorine Meurent — who was also a musician and an artist in her own right — was not just known but well-known in Paris.

|

| Édouard Manet, Olympia (1863) |

Many French artists felt not only sympathy but certain solidarity with demimondaines.

|

| Edgar Degas, La fête de la patronne (1878–1879) |

|

| Édouard Manet, Nana (1877) |

For Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, just like for Degas, Rops and Van Gogh, the brothels were a source of inspiration. According to his biography,

Toulouse-Lautrec spent much time in brothels, where he was accepted by the prostitutes and madams to such an extent that he often moved in, and lived in a brothel for weeks at a time. He shared the lives of the women who made him their confidant, painting and drawing them at work and at leisure.

|

| Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Au Salon de la rue des Moulins (1894) |

Children and nymphets

In the “group selfie” of Franz von Lenbach family, the artist’s wife and daughters stare at us with an “absolutely malevolent expression”; the younger girl is a femme fatale in the making.

|

| Franz von Lenbach, Selbstbildnis mit Frau und Töchtern (1903) |

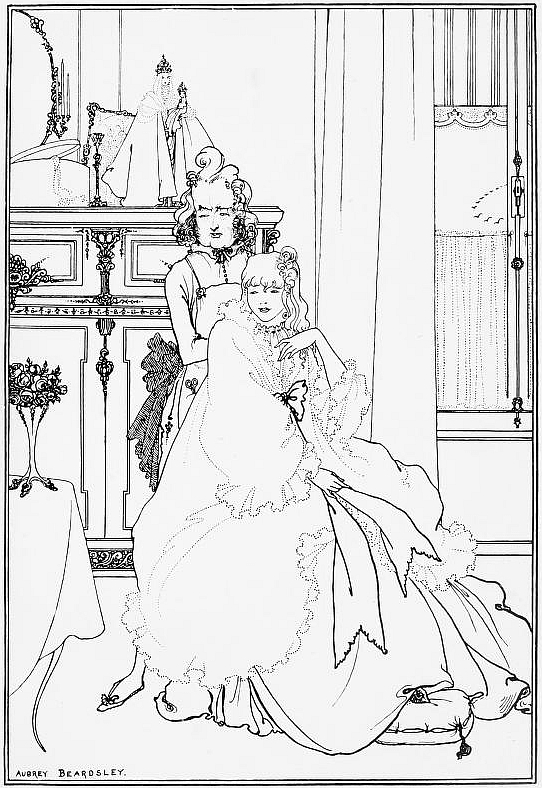

The Coiffing is an illustration by Aubrey Beardsley’s illustration to his own, pretty disturbing, poem The Ballad of a Barber.

|

| Aubrey Beardsley, The Coiffing (1896) |

A pre-adolescent girl in A Venetian Bather by Paul Peel (1889) treads the fine line between innocence (of a child) and erotism (of Venus with a mirror).

|

| Paul Peel, A Venetian Bather (1889) |

Uncertain sex

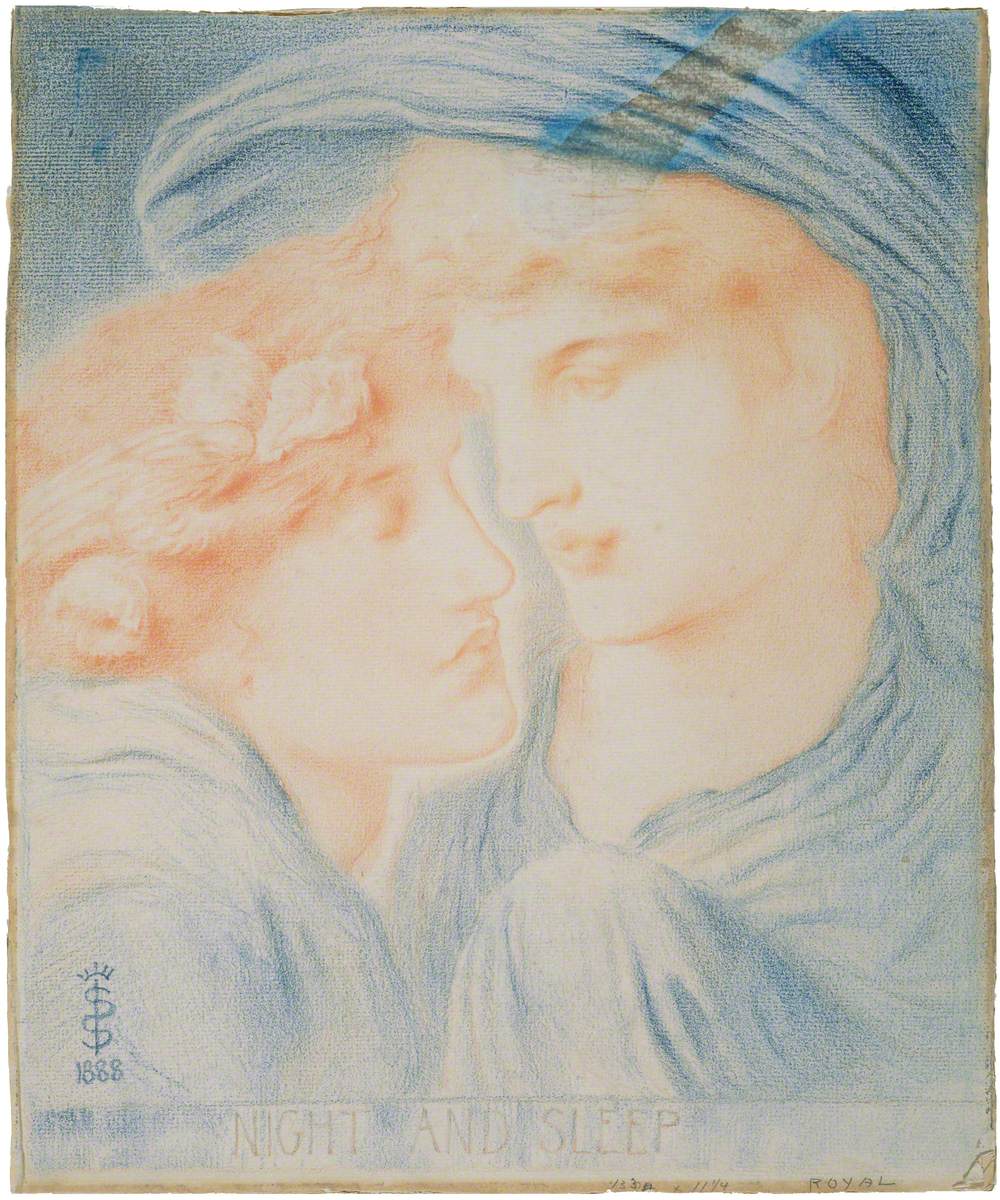

The androgynous figures appear frequently in the late 19th-century art, most importantly in Symbolist works. It represented an absolute, ideal, self-sufficient beauty.

|

| Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Morning Music (1864) |

|

| Simeon Solomon, Night and Sleep (1888) |

Sapphic love

Le Sommeil, as well as another Courbet’s painting, L’Origine du monde, was commissioned by Halil Şerif Pasha for his private collection. No, these ladies are not femmes fatales. They aren’t out there luring hapless men to perdition. Why should they be interested in men at all?

|

| Gustave Courbet, Le Sommeil (1866) |

Ditto Rodin’s Femmes damnées: they have a lot of fun on their own.

|

| Auguste Rodin, Femmes damnées (1885–1890) |

La Punizione della Lussuria (The Punishment of Lust) by Giovanni Segantini, like his other work, Le cattive madri (The Bad Mothers), deals with the subject of women who forsake their “natural” role, that is, to be a mother.

|

| Giovanni Segantini, La Punizione della Lussuria (1891) |

Motherhood

Who is a good mother then? Why, a woman who is closest to the impossible ideal of virgin mother, of course. Hardly the one portrayed by Edvard Munch in a series of paintings known as Madonna. It is unclear whether Munch actually meant her to be a representation of Virgin Mary. Bornay has chosen for her book the litograph that is distinguished from the other versions by a sort of frame complete with wriggling spermatozoa and a glum-looking foetus.

|

| Edvard Munch, Madonna (1895–1902) |

Death is a woman

Это абсурд, враньё: Иосиф Бродский, «Натюрморт» |

Skull, skeleton, sickle in hand — Joseph Brodsky, Nature Morte

(translated by Andrey Kneller) |

If your common or garden femme fatale may be perilous, the ladies painted by Thomas Cooper Gotch and Carlos Schwabe are Death personified. When you see one, you’ll know.

|

| Thomas Cooper Gotch, Death the Bride (1894–1895) |

And what if it was not male fears but genuine fascination with death — as well as with strong women — that was driving these artists? Just a thought.

|

| Carlos Schwabe, La Mort et le Fossoyeur (1900) |

For a more up-to-date take on this topic, see Die Femme fatale in der Kunst: Ein Mythos und seine Demontage (The Femme Fatale in Art: A Myth and its Deconstruction), a documentary by Susanne Brand.

| * | I have to say that towards the end of the book it goes more smoothly. Either I got used to this kind of language or the author got tired of her own style and started to write in shorter sentences. |

No comments:

Post a Comment