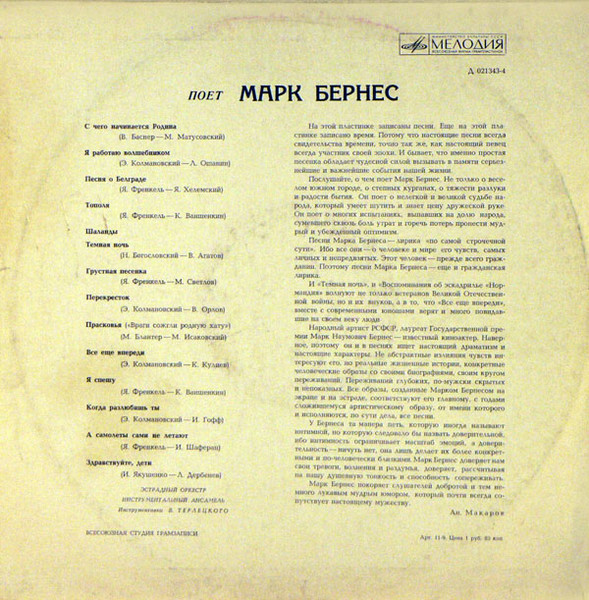

Very different from Les Grandes Musiques de Films but equally loved by my mum was an LP called simply «Поёт Марк Бернес» (Mark Bernes sings). Since the mid-seventies, although she was perfectly able to put it on the turntable, my mum would rather ask my brother or me to do it. As a result, the vinyl was scratched beyond any reason. So yes, another record I grew up listening to and damaging it in the process.

On the sleeve, a black and white photo of a middle-aged man holding a mike. Back then, I’d probably say “an old man”. Old? The album was released in 1968; Mark Naumovich Bernes (Марк Наумович Бернес) died the following year aged 57.

I myself would never call Bernes «певец» (singer) — I felt that word was reserved for the likes of Iosif Kobzon, Lev Leshchenko or Muslim Magomayev. Bernes was a chansonnier. He was not singing his heart out but talking, joking, telling a story.

I can’t listen to this disc now with the same ears as 50 years ago. The opener, «С чего начинается Родина» (What Does the Homeland Begin With), just makes me cringe. I can live with most of the lyrics — I mean, it’s all right, not worse than a typical Anglophone pop song — such as the one of surprisingly jazzy «Всё ещё впереди» (Everything is Still to Come). Two tracks, however, are unquestionable masterpieces: «Тёмная ночь» (Dark is the Night) and «Шаланды, полные кефали» (Scows Full of Mullet)*, both composed by Nikita Bogoslovsky with lyrics by Vladimir Agatov for the 1943 film «Два бойца» (Two Soldiers). The songs in the movie sound quite different from those on the 1968 record. For example, in the “original” «Шаланды» Bernes pronounced the name Odessa as «Одэсса» /ɐˈdɛsːə/ while in the ’60s rendition it’s the normative «Одесса» /ɐˈdʲesːə/. Imprinting and all, I still prefer the latter version†.

As for «Тёмная ночь», it deservedly became one of the most famous and beloved Soviet songs created during the Great Patriotic War... and that despite neither being patriotic nor mentioning the war. Yes, we know, the war is raging on — in the film. Bullets, mortal combat, death are all present, but there is no word “war” in the lyrics. And so the song transcends time, place and circumstances. An immortal classic.

| * | Curiously, the word шаланда comes from the French chaland (barge), and that, in its turn, from Ancient Greek χελάνδιον; кефаль (mullet) from κέφαλος; and Одесса (Odessa) itself was named after the ancient Greek city of Odessos (Ὀδησσός). |

| † | According to Nikita Bogoslovsky, «Шаланды», its success notwithstanding, was harshly criticised by Soviet bureaucrats (who likened the song to criminal folklore) and not recommended for official performances. |

No comments:

Post a Comment