In Russian, possessive pronouns (притяжательные местоимения) agree with the noun of the possessed, or possessee, in case, gender, and number. To be more precise, this is the case for the first person, мой (my), наш (our), твой (thy) and ваш (your). In the third person singular, we don’t care about case, gender, and number of the possessee anymore, however the distinction is made between masculine and neuter его (his, its) and feminine её (her). Finally, for the third person plural possessor, the unique form их (their) is used. You can’t go wrong with их. Well, almost.

| Possessor | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number → | Singular | Plural | Self | |||||||

| Person → | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| m | n | f | ||||||||

| Possessee | ||||||||||

| Nominative | m | мой | твой | его | его | её | наш | ваш | их | свой |

| n | моё | твоё | его | его | её | наше | ваше | их | своё | |

| f | моя | твоя | его | его | её | наша | ваша | их | своя | |

| pl | мои | твои | его | его | её | наши | ваши | их | свои | |

| Genitive | m | моего | твоего | его | его | её | нашего | вашего | их | своего |

| n | моего | твоего | его | его | её | нашего | вашего | их | своего | |

| f | моей | твоей | его | его | её | нашей | вашей | их | своей | |

| pl | моих | твоих | его | его | её | наших | ваших | их | своих | |

| Dative | m | моему | твоему | его | его | её | нашему | вашему | их | своему |

| n | моему | твоему | его | его | её | нашему | вашему | их | своему | |

| f | моей | твоей | его | его | её | нашей | вашей | их | своей | |

| pl | моим | твоим | его | его | её | нашим | вашим | их | своим | |

| Accusative | m animate | моего | твоего | его | его | её | нашего | вашего | их | своего |

| m inanimate | мой | твой | его | его | её | наш | ваш | их | свой | |

| n | моё | твоё | его | его | её | наше | ваше | их | своё | |

| f | мою | твою | его | его | её | нашу | вашу | их | свою | |

| pl animate | моих | твоих | его | его | её | наших | ваших | их | своих | |

| pl inanimate | мои | твои | его | его | её | наши | ваши | их | свои | |

| Instrumental | m | моим | твоим | его | его | её | нашим | вашим | их | своим |

| n | моим | твоим | его | его | её | нашим | вашим | их | своим | |

| f | моей | твоей | его | его | её | нашей | вашей | их | своей | |

| pl | моими | твоими | его | его | её | нашими | вашими | их | своими | |

| Prepositional | m | моём | твоём | его | его | её | нашем | вашем | их | своём |

| n | моём | твоём | его | его | её | нашем | вашем | их | своём | |

| f | моей | твоей | его | его | её | нашей | вашей | их | своей | |

| pl | моих | твоих | его | его | её | наших | ваших | их | своих | |

The word Ваш (capitalised in written Russian) is the polite form of second-person singular or plural possessive pronoun. Grammatically, it behaves exactly like ваш, even if you address just one person, for example «Ваше величество» (Your Majesty). When we talk about the single royal, say the Queen, in the third person, we should utilise the third person singular, i.e. «её величество» (Her Majesty), not «их величество», if we don’t want to sound illiterate. Note that Russian styles such as величество (Majesty), высочество (Highness), сиятельство, светлость, превосходительство (Excellency), преосвященство (Holiness) etc. are invariably neuter.

The reflexive-possessive pronoun свой does not have analogue in English. It always points to the subject of the sentence irrespectively of the person, gender, and number of that subject. It could be roughly translated as “one’s own”... except that “own” has its own exact analogue, собственный. This latter is used to amplify the sense of possession, so свой собственный stands for “one’s very own”.

With свой, we avoid possible tautology. For example, «у тебя есть своя машина» is better than somewhat repetitive «у тебя есть твоя машина». Another reason to use свой is to sound a bit less personal. In the sayings like «своя рубашка ближе к телу», the subject (the owner of this proverbial shirt) is not identified, probably because «моя рубашка ближе к телу» would sound too mean. It sounds mean enough as it is.

Russian possessive pronouns can be nominalised as to refer to (a group of) people. For example, the word наши also means “our people” and in times of war was often used as an antonym of враги “enemy”. The idiom «и нашим и вашим» (literally, “both to ours and to yours”) is a (shorter!) Russian equivalent of “hold with the hare and run with the hounds”. Likewise, свой or свои could mean “one’s kin” or “friend” as in «Свой среди чужих, чужой среди своих», “At home among strangers, a stranger among his own”.

| Моей душе покоя нет | My heart is sair |

| Сын или Бог, я твой | Son or God, I’m thine |

| Первая его работа вызвала большой шум. | His first work caused quite a stir. |

| Но, к великому её сожалению, банка оказалась пустой. | But to her great disappointment it was empty. |

| Отче наш | Our Father |

| Их нравы | Their morals |

| Свои люди — сочтёмся | It’s a Family Affair — We’ll Settle It Ourselves |

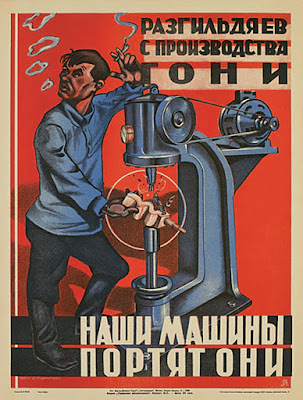

The Soviet-era posters used a lot of наш while reserving их for the enemy.

|

| Разгильдяев с производства гони: наши машины портят они Kick the slobs out of the production line, they damage our machinery |

|

| Трудовой народ, строй свой Воздухофлот Workers, build your own Air Fleet |

|

| Ребята! Ваша шалость с огнём приводит к пожару Children! Your messing around with fire leads to conflagration |

|

| Добьём немецко-фашистских захватчиков в их берлоге! Let’s finish off the Nazi invaders in their lair! |

No comments:

Post a Comment